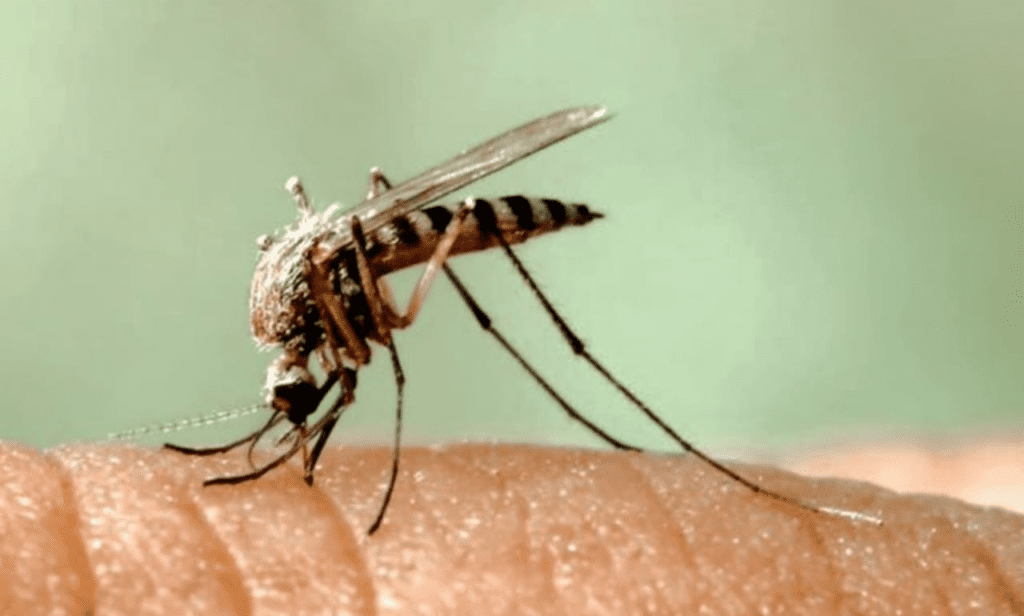

Health officials in Fulton County, Georgia, just confirmed that mosquitoes collected from surveillance sites tested positive for West Nile virus (WNV). This detection signals the virus is actively circulating in local mosquito populations, heightening risks for human transmission. While no human cases have been reported yet this season, the discovery triggers urgent public health alerts. Summer’s heat and humidity create ideal breeding conditions for mosquitoes, particularly the Culex species known to carry WNV. Fulton County’s Board of Health is intensifying mosquito trapping and testing across neighborhoods, urging residents to eliminate standing water sources like flower pots, gutters, and birdbaths where mosquitoes lay eggs.

West Nile virus might sound like a distant threat, but it’s the leading mosquito-borne disease in the continental U.S. since its arrival in 1999. Dr. Sandra Valenciano, an epidemiologist with the CDC, explains, “WNV thrives in urban and suburban ecosystems. It cycles between birds and mosquitoes—humans are accidental hosts when infected mosquitoes bite us.” Most infections (about 80%) cause no symptoms, but 20% of people develop flu-like signs: fever, headache, body aches, joint pain, or vomiting. Roughly 1% progress to severe neuroinvasive disease—like encephalitis or meningitis—which can lead to paralysis, brain damage, or death. Older adults and immunocompromised individuals face the highest risks.

Fulton County’s detection fits a predictable seasonal pattern. Cases typically peak in late summer through fall. Georgia reported 42 human WNV cases and 3 deaths in 2023, according to state health data. Nationally, the CDC tallies 2,500–10,000 annual symptomatic cases, though experts believe this is underreported. “Surveillance is our radar,” says Dr. Lynette Phillips, a public health entomologist. “Finding WNV in mosquitoes means we must act before people get sick.” Local responses include larvicide treatments in storm drains and public education blitzes.

So why should Fulton County residents pay attention now? Mosquitoes that transmit WNV are most active at dawn and dusk. A single bite from an infected mosquito is all it takes. Unlike diseases with vaccines or specific treatments, WNV has neither. Hospitals manage severe cases with supportive care—IV fluids, breathing assistance, and pain relief. Recovery can take months, and some neurological effects linger permanently. A 2019 study in The New England Journal of Medicine found that 40% of severe WNV patients still had mobility or cognitive issues a year later.

Protection hinges on avoiding bites. Health officials emphasize the “Four Ds”:

- Drain standing water weekly (even bottle caps can breed mosquitoes).

- Dress in long sleeves and pants outdoors.

- Defend with EPA-approved repellents like DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus.

- Dusk/Dawn—limit outdoor activity when mosquitoes swarm.

Atlanta’s dense tree canopy and frequent rain create abundant mosquito habitats. “One neglected pool or clogged gutter can produce thousands of mosquitoes,” warns Fulton County environmental health director Marcus Johnson. “Community cooperation is non-negotiable.” Beyond personal precautions, countries use GIS mapping to target high-risk zones. Traps set in parks and residential areas collect mosquitoes for species identification and virus testing—a frontline defense revealing where spraying or larval control is needed.

Historically, outbreaks surge after unusually wet springs or hot summers. In 2012, a U.S. outbreak sickened 5,674 people—the worst year on record. Texas, hit hardest, declared a state of emergency. Climate models suggest rising temperatures could expand WNV’s reach into new regions. “Warmer winters mean earlier mosquito seasons and longer transmission windows,” notes climate health researcher Dr. Aaron Bernstein.

Critically, WNV doesn’t spread person-to-person or through handling live/dead birds. But finding dead birds—especially crows, jays, or raptors—can indicate local virus activity. Georgia’s Department of Public Health tracks these reports for surveillance. If you spot multiple dead birds, contact county health officials—but don’t touch the birds barehanded.

For those infected, symptoms usually appear 3–14 days post-bite. Mild cases resolve with rest and hydration. Severe symptoms—high fever, neck stiffness, disorientation, tremors—demand immediate ER care. Diagnostic tests include blood or spinal fluid checks for antibodies. Survivors like David Carter, who contracted WNV in DeKalb County in 2020, describe the ordeal as “waking up paralyzed.” After months of rehab, he still has limited arm mobility. “I never thought a mosquito could do this,” he says.

Public health funding cuts complicate responses. Mosquito control programs rely heavily on local budgets. A 2023 National Association of County and City Health Officials survey found 30% of vector control units lack adequate staffing. “Prevention is cost-effective,” insists Dr. Valenciano. “Every dollar spent on mosquito control saves $14 in healthcare costs.”

Beyond WNV, mosquitoes in Georgia carry other threats like Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) and La Crosse virus. Yet WNV remains the most pervasive. The Fulton County detection is a regional wake-up call. Neighboring counties—Cobb, DeKalb, Gwinnett—often report cases within weeks. “Mosquitoes don’t respect county lines,” says Phillips.

Urban development amplifies risks. As Atlanta expands, pavement and concrete create water-holding debris where Culex mosquitoes thrive. “Overgrown lots and construction sites are epidemic incubators,” Johnson stresses. Code enforcement and neighborhood clean-ups are part of the strategy.

Travelers should also stay alert. WNV is endemic across all 48 contiguous states. Cases have been reported this summer in Arizona, California, and Colorado. The CDC advises standard mosquito precautions nationwide.

Misconceptions persist. Some believe aerial spraying alone solves outbreaks, but ground-level source reduction is irreplaceable. Others assume cold snaps eliminate risks, but mosquitoes can overwinter in sheltered spots. “There’s no off-season for vigilance,” says Phillips.

Looking ahead, research explores novel controls like genetically modified mosquitoes or targeted vaccines. Until then, prevention is paramount. “This isn’t about fear—it’s about empowerment,” says Dr. Valenciano. “Simple actions save lives.”

Fulton County will continue weekly mosquito testing through October. Results are posted on the health department’s website. Residents can request property inspections or report neglected swimming pools. Free repellent is distributed at community clinics in high-risk ZIP codes. Collaboration with Emory University and the CDC enhances data analysis and response agility.

Ultimately, WNV is a shared battle. Installing window screens, using fans on porches to disrupt mosquitoes, and opting for permethrin-treated clothing during hikes reduce exposure. Pediatrician Dr. Lisa Chen advises parents: “Repellents are safe for kids over 2 months. Don’t skip protection during evening sports practices.”

The economic toll includes medical bills and lost productivity. A Johns Hopkins study estimated average hospitalization costs at $25,000 per WNV patient. Insurance gaps can burden families—another reason prevention matters.

Globally, climate change and urbanization make mosquito-borne diseases a growing priority. The World Health Organization lists WNV as a neglected tropical disease needing scalable interventions. Lessons from Fulton County’s proactive stance—like real-time surveillance and community mobilization—offer blueprints for high-risk areas worldwide.

For now, metro Atlanta residents should heed health alerts. “We’re not sounding alarms without cause,” Johnson states. “This detection means the threat is real and present. Protect yourselves today—don’t wait for a human case to act.”