Virus infections are a common part of the human experience, but what if one of the most widespread viruses on the planet was secretly laying the groundwork for a serious autoimmune disease years later? This isn’t science fiction; it’s a compelling and growing area of scientific research centered on the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). For millions, particularly those with lupus, this common childhood infection may have been the first, critical step on a path toward their chronic condition.

The Unseen Ubiquity of Epstein-Barr Virus

To understand the potential link, one must first appreciate the sheer prevalence of EBV. It is a member of the herpesvirus family and is astonishingly common. By the time adults reach the age of 40, it’s estimated that over 95% of the population has been infected. For many, this infection occurs in early childhood with few or no symptoms. In others, particularly teenagers and young adults, it manifests as mononucleosis, or “mono,” bringing with it debilitating fatigue, fever, and sore throat.

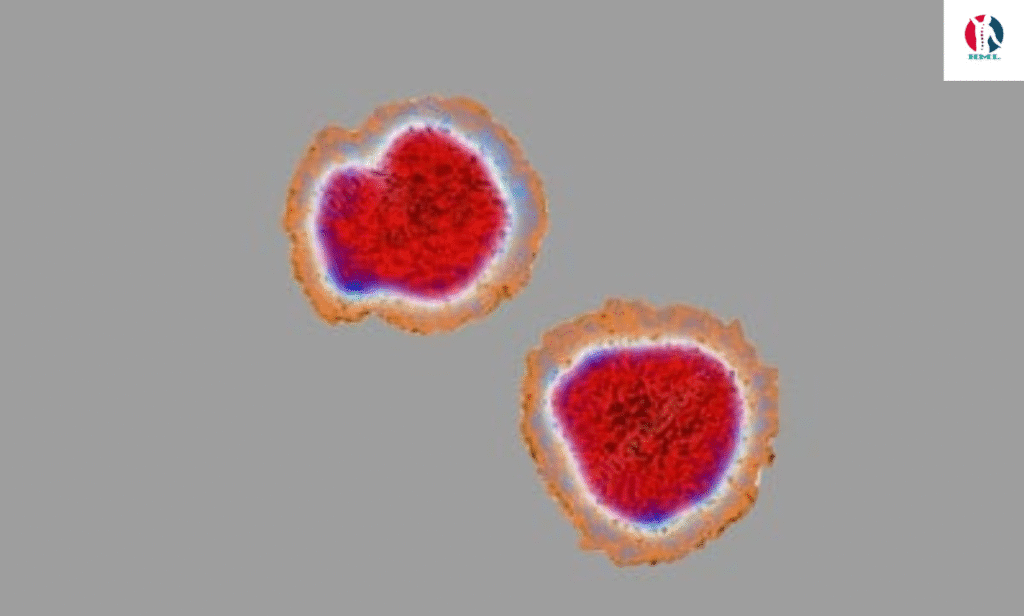

After the initial infection, the virus doesn’t leave the body. Like its herpesvirus cousins, it becomes a lifelong resident, retreating into a dormant state within our own immune cells called B-cells. For most people, the immune system keeps the virus in a permanent checkmate, and it causes no further issues. The question that has long intrigued scientists is: what happens when this delicate truce is broken?

The Enigma of Lupus: A Case of Mistaken Identity

Lupus, specifically systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is a complex and chronic autoimmune disease. In autoimmune conditions, the body’s sophisticated defense system, designed to attack foreign invaders like bacteria and viruses, turns its weapons on its own tissues. In the case of lupus, this can lead to inflammation and damage affecting virtually any part of the body—the skin, joints, kidneys, heart, lungs, and brain.

The fundamental problem in lupus is a loss of self-tolerance. The immune system fails to recognize the body’s own cells and proteins as “self” and mistakenly labels them as dangerous “non-self.” This triggers a cascade of immune attacks, leading to the wide-ranging and often debilitating symptoms of the disease. For decades, researchers have been trying to pinpoint the exact trigger for this mistaken identity. Genetics play a role, but they don’t tell the whole story, as not everyone with a genetic predisposition develops lupus. There must be an environmental trigger, and a growing body of evidence suggests EBV is a prime suspect.

The Molecular Mimicry Hypothesis: A Case of Friendly Fire

One of the leading theories explaining the EBV-lupus connection is a phenomenon known as “molecular mimicry.” Imagine a spy who perfectly mimics the appearance and mannerisms of a friendly agent to gain access to a secure facility. In a similar way, certain proteins produced by the Epstein-Barr virus bear a striking structural resemblance to proteins naturally found in the human body.

Here’s how it might unfold:

- Initial Infection: The body is infected with EBV.

- Immune Response: The immune system, doing its job, creates powerful antibodies specifically designed to target and neutralize the EBV proteins.

- Cross-Reaction: However, because the viral protein and a human protein (in this case, one called EBNA-1) look so similar, the antibodies get confused. They can’t distinguish between the virus and the body’s own cells.

- Autoimmunity Begins: These misguided antibodies then begin to attack the body’s healthy tissues, seeing them as the enemy. This “friendly fire” is believed to be a key driver of the autoimmune damage seen in lupus.

A landmark 2018 study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation provided strong evidence for this. Researchers discovered that a specific antibody in lupus patients, which targets the body’s own DNA (a classic hallmark of the disease), initially develops to target an EBV protein called EBNA-1. The antibody then cross-reacts with a human protein, kickstarting the autoimmune process.

Beyond Mimicry: The Viral “On Switch” for Genes

Molecular mimicry is a powerful explanation, but it may not be the only way EBV influences lupus. Another compelling theory involves the virus’s ability to manipulate our genetics. EBV is a master of hijacking the machinery of the B-cells it infects. When it enters a B-cell, it releases a protein that acts like a master switch, turning on a range of human genes.

Some of these genes are involved in the normal immune response, but crucially, many of the genes that EBV switches on are the same ones associated with a higher genetic risk for developing lupus. In essence, the virus may be flipping the “on” position for the very genetic pathways that predispose a person to the disease. It’s not changing the genes themselves, but it is activating them, potentially pushing a genetically susceptible individual from a state of risk into a state of active disease.

Dr. John Harley, a leading researcher in the field from the Center for Autoimmune Genomics and Etiology, has described EBV’s role as “setting the table” for autoimmunity. The genetic risk is there, and the virus comes along and lays out all the place settings, making an autoimmune reaction much more likely to occur.

Statistics and the Smoking Gun

The epidemiological evidence linking EBV and lupus is difficult to ignore. Multiple studies have shown that nearly 100% of lupus patients have been infected with EBV, compared to about 95% of the general population. While this 5% difference may seem small, it is statistically significant. More tellingly, studies analyzing blood samples taken from individuals before they developed lupus found that EBV infection almost always preceded the onset of the disease. In one study, the risk of developing lupus was about 50 times higher in individuals who had been infected with EBV.

This temporal relationship—infection first, diagnosis later—is a critical piece of the puzzle. It suggests that EBV is not a mere passenger in people who happen to have lupus, but rather a potential instigator.

Implications for the Future: Prevention, Treatment, and a Path Forward

Understanding the precise role of EBV in lupus is more than an academic exercise; it has profound implications for the future of managing this disease.

- Vaccination: The holy grail of this research is the development of an effective vaccine against EBV. While no such vaccine is currently available, several are in various stages of development. A successful EBV vaccine could, in theory, dramatically reduce the incidence of lupus in future generations, much like the HPV vaccine has reduced cervical cancer rates. This would be a monumental step from treatment to prevention.

- Novel Therapeutics: For those already living with lupus, this knowledge opens up new avenues for treatment. Instead of using broad-spectrum immunosuppressants that dampen the entire immune system (with significant side effects), researchers could develop highly targeted therapies. These could include drugs that:

- Block the specific cross-reactive antibodies.

- Prevent the virus from reactivating in B-cells.

- Interfere with the viral proteins that manipulate human genes.

- Personalized Medicine: It could also lead to more personalized approaches. Doctors could potentially screen individuals with a strong family history of lupus for their EBV status and immune response, allowing for earlier monitoring and intervention.

It is crucial to remember that EBV is likely not the sole cause of lupus. The prevailing model is the “multiple-hit hypothesis.” An individual may have a genetic predisposition (the first hit), then contracts EBV (the second hit), and perhaps later encounters another environmental trigger like hormonal changes, sunlight, or another infection (a third hit), which finally pushes the immune system over the edge into full-blown autoimmune disease. EBV appears to be a critical, and perhaps necessary, piece of this complex puzzle.

The investigation into the link between a common virus and a devastating autoimmune disease represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of health and illness. It blurs the line between infectious disease and chronic internal disorder. While much work remains to be done, the connection between the Epstein-Barr virus and lupus offers a beacon of hope—a clear biological target that could one day lead to a world with fewer lupus diagnoses and better, smarter treatments for those who live with it.