In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States—a landmark achievement for modern medicine. Fast-forward to today, and the disease is making an alarming comeback. Health officials are sounding the alarm as measles cases surge across the country, with Texas emerging as a hotspot. This outbreak isn’t just a local issue; it reflects a broader national—and global—trend fueled by declining vaccination rates, misinformation, and gaps in public health strategies. Let’s unpack what’s happening, why it matters, and how communities are responding.

The Resurgence of a Preventable Disease

Measles, a highly contagious viral infection, spreads through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Symptoms include high fever, cough, runny nose, and the telltale red rash. While most people recover, complications like pneumonia, brain swelling, and even death can occur, particularly in unvaccinated children and immunocompromised individuals.

Before the measles vaccine was introduced in the 1960s, the U.S. saw 3–4 million cases annually. Widespread vaccination reduced that number to near zero by the early 2000s. But recent data tells a different story: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported over 120 measles cases across 17 states in the first quarter of 2024 alone—a threefold increase compared to the same period in 2023. Texas, with its rapidly growing outbreak, accounts for nearly 30% of these cases.

Texas: Ground Zero for the Latest Outbreak

Texas has reported 45 confirmed measles cases since January 2024, primarily clustered in urban areas like Houston and Austin. One of the largest clusters originated at a Fort Worth elementary school where multiple students—most unvaccinated—contracted the virus. The school temporarily closed for deep cleaning and contact tracing, but the outbreak had already spilled into nearby communities.

Dr. Melissa Stokos, a Texas-based epidemiologist, explains, “Measles is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 90% of unvaccinated individuals close to that person will also become infected.” This statistic underscores the danger in communities with low vaccination rates. In Texas, only 89% of kindergarteners are fully vaccinated against measles, below the 95% threshold needed for herd immunity—the point where enough people are immune to stop the virus from spreading.

Why Is Measles Spreading Again?

Three key factors are driving the resurgence:

- Declining Vaccination Rates:

Vaccination coverage has slipped nationwide, partly due to the “anti-vax” movement and misinformation linking the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine to autism—a claim repeatedly debunked by research. In Texas, parents can easily opt out of school-required vaccines for “reasons of conscience,” creating pockets of vulnerability. - Global Travel:

Measles remains common in parts of Africa, Asia, and Europe. Unvaccinated travelers can bring the virus back to the U.S., sparking outbreaks in under-protected communities. - Post-Pandemic Challenges:

COVID-19 disrupted routine childhood vaccinations. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 40 million children missed measles vaccines globally in 2022, leaving many unprotected.

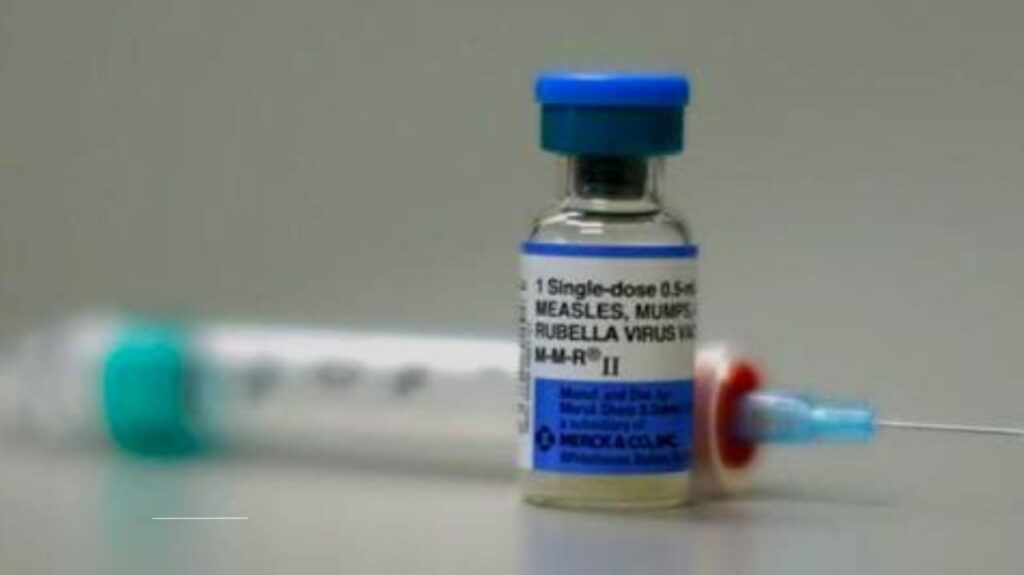

The Lifesaving Role of the MMR Vaccine

The MMR vaccine is safe and 97% effective at preventing measles with two doses. “Vaccines are victims of their own success,” says Dr. Paul Offit, an infectious disease expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “Because people haven’t seen measles firsthand, they underestimate its risks.”

Despite the evidence, vaccine hesitancy persists. A 2023 National Institutes of Health (NIH) survey found 12% of U.S. parents delay or skip vaccines for their children, often due to safety fears. Public health campaigns are now emphasizing the vaccine’s track record: Over 500 million doses have been administered worldwide since the 1970s, with severe side effects occurring in less than 1 per million cases.

How Health Officials Are Responding

To contain outbreaks, states are deploying a mix of strategies:

- Quarantines: Unvaccinated individuals exposed to measles are asked to isolate for up to 21 days.

- Pop-Up Clinics: Texas opened temporary vaccination sites in high-risk neighborhoods, offering free MMR doses.

- Public Awareness Campaigns: The CDC launched social media initiatives to counter misinformation, partnering with influencers and pediatricians.

Still, challenges remain. Not all states share real-time data on outbreaks, complicating response efforts. And with measles’ 10–14 day incubation period, cases can go undetected until they’ve already spread.

Measles Symptoms and Risks: What to Watch For

Early symptoms mimic a common cold: fever, cough, and red, watery eyes. After 2–3 days, tiny white spots (Koplik spots) may appear inside the mouth, followed by a red rash that spreads from the face downward.

While most recover in 7–10 days, 1 in 5 unvaccinated children are hospitalized. Measles can also cause long-term immune system damage, leaving survivors vulnerable to other infections for years—a phenomenon called “immune amnesia.”

The Path Forward: Bridging Gaps in Immunity

Rebuilding herd immunity requires a multi-pronged approach:

- Strengthening School Vaccine Requirements: States like California and New York have eliminated non-medical exemptions, a policy Texas is now debating.

- Community Engagement: Trusted local leaders, including religious figures and teachers, are being trained to address vaccine concerns.

- Global Cooperation: The WHO aims to boost global measles vaccination coverage to 95% by 2030, which would reduce cross-border risks.

As the Texas outbreak continues, health experts stress that measles isn’t a relic of the past—it’s a present danger. But with robust vaccination efforts and public cooperation, it’s a threat we can still overcome.