Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal cancers, yet its screening remains limited due to its rarity. Despite being the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, widespread screening isn’t feasible because pancreatic cancer doesn’t occur as frequently as other cancers like breast or colon cancer. This unique challenge has led to a more targeted approach, focusing on specific high-risk groups.

Dr. Brian M. Wolpin, MD, MPH, a leading expert in gastrointestinal cancers and the director of the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, explains that pancreatic cancer screening is not broadly implemented. Unlike breast cancer mammograms or colonoscopies for colon cancer, pancreatic cancer lacks an age-based screening protocol. Instead, screenings are reserved for two main groups: individuals with a strong family history or genetic risks and patients with pancreatic cysts.

One of the primary groups recommended for pancreatic cancer screening includes individuals with a significant family history of the disease. Dr. Wolpin emphasizes that inherited genetic mutations play a critical role in determining the risk of pancreatic cancer. Mutations in genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and others can predispose individuals to the disease. People who inherit these mutations from their parents are more likely to develop pancreatic cancer during their lifetime. For these patients, early detection is crucial, and screening is often recommended at specialized clinics equipped to handle high-risk cases.

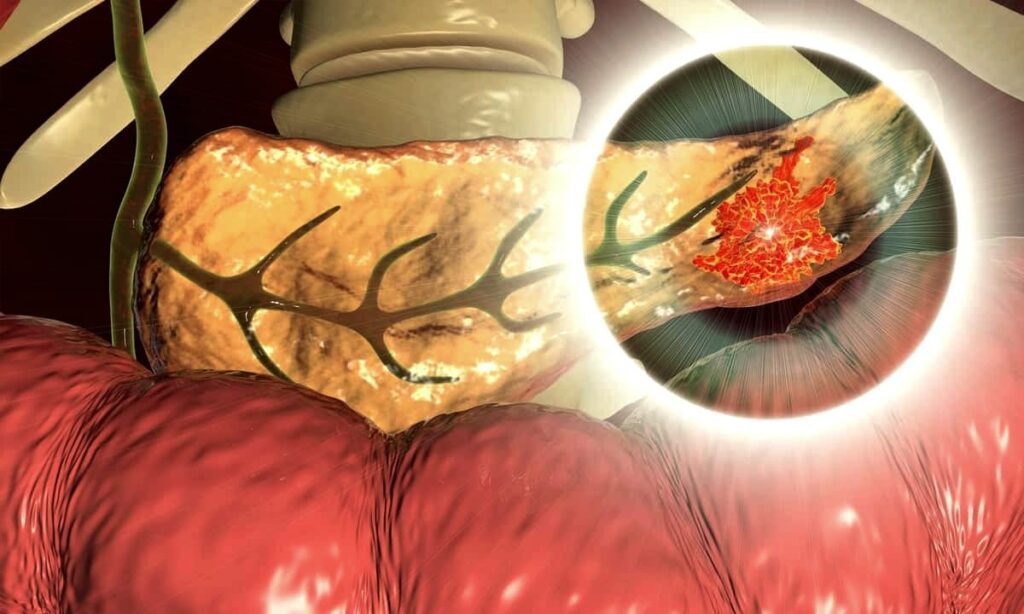

These screenings are typically conducted using advanced imaging techniques like endoscopic ultrasound and MRI. These methods provide detailed visuals of the pancreas, allowing healthcare professionals to identify potential abnormalities early. Specialized clinics, often based at academic medical centers, are at the forefront of providing these services to high-risk individuals.

Another group that often undergoes pancreatic cancer screening includes patients with pancreatic cysts. These cystic lesions, which can be detected through imaging scans, are relatively common. However, not all cysts pose a risk of turning cancerous. While most cysts are benign and will never lead to cancer, a subset of them has the potential to become malignant.

Approximately 10% to 15% of pancreatic cancers originate from cystic lesions. To address this risk, healthcare providers rely on a set of established guidelines to determine which cysts should be monitored. These guidelines are based on factors such as cyst size, the presence of specific symptoms, and the results of imaging studies. Patients with cysts deemed at higher risk of becoming cancerous are often advised to undergo regular monitoring.

Pancreatic cancer’s high lethality underscores the importance of identifying and monitoring at-risk populations. As Dr. Wolpin highlights, this selective approach is necessary because of the disease’s relatively low incidence. Unlike breast or colon cancer, where age-based screenings are routine, pancreatic cancer requires a more nuanced method to ensure that resources are directed toward individuals with the greatest likelihood of developing the disease.

Through initiatives such as those at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and similar institutions, researchers and clinicians are working to refine and expand the tools available for pancreatic cancer risk assessment. This includes improving imaging techniques, developing better guidelines for cyst monitoring, and advancing genetic testing methods to identify high-risk individuals. These efforts aim to enhance early detection rates and, ultimately, improve outcomes for patients with or at risk of pancreatic cancer.