Colon cancer doesn’t present or develop identically in men and women—a nuance that, when better understood, can make a real difference in detection and outcomes. As an oncologist deeply invested in both research and patient care, I’ve found that appreciating these subtle distinctions empowers individuals to make informed choices and helps clinicians tailor strategies for each patient’s unique profile.

Men consistently face a higher risk of developing colon cancer than women. In fact, some studies suggest that males have a 30 – 50 percent greater likelihood of developing colorectal cancer during their lifetime compared to female counterparts. In India, the gap is even more noticeable: population cancer registries reveal that males face almost twice the lifetime risk that females do, with lifetime risk estimations ranging from one in 167 to one in 250 for men, while for women it spans between one in 167 and one in 500. These numbers may reflect lifestyle disparities—higher tobacco and alcohol use, greater consumption of red and processed meats, and typically lower fiber intake among men—but they also prompt us to closely examine biological differences.

Hormonal influences appear to shield women to a degree. Estrogen has been posited as protective against early colon cancer development, though once women reach menopause, that protective effect wanes. It’s compelling to note that after menopause, women are more likely to develop right-sided colon cancers, which often have subtler symptoms and a more aggressive nature, contributing to delayed diagnosis and poorer prognosis.

Digging deeper, metabolomic studies from Yale have illuminated how tumors themselves differ between sexes. Women with right-sided tumors show elevated levels of fatty acid oxidation, glutamine, and asparagine—metabolic pathways linked to more aggressive cancer growth—while men’s tumors tend toward lactate-driven metabolism. This isn’t just academic; it reshapes how we view risk and may eventually influence precision treatment.

When it comes to symptoms, colon cancer largely affects both genders in similar ways—changes in bowel habits (constipation, diarrhea, or alternating patterns), unexplained weight loss, fatigue, blood in stool (bright red or darker tarry types), abdominal discomfort, a sense of incomplete bowel movement, or even iron-deficiency anemia. That said, women may experience more vague or misattributable symptoms—persistent fatigue, weight loss, or menstrual irregularities tied to anemia can lead to misattribution, thereby delaying specialist referral.

Research also reveals that women may delay reporting or seeking evaluation for symptoms longer than men, whereas men might be nudged by family or partners sooner. This behavioral nuance, combined with a tendency of tumors to grow on the right side in women, can conspire to push diagnosis to later stages, impacting the effectiveness of treatment.

Epidemiological observations are sobering. While colon cancer is still more common in older adults, there’s a troubling upswing in younger populations, especially among those under 50. Incidence among people aged 20–39 has climbed steadily (1–2.4 percent annually), and those aged 20–29 have seen rectal cancer rise by over 3 percent per year in recent decades. Celebrities and case studies underline this: for example, a healthy 34-year-old fitness enthusiast discovered stage 3 colon cancer when he noticed blood in his stool; now cancer-free, he urges early evaluation at the first sign. Similarly, actor James Van Der Beek, diagnosed at 48, regrets attributing his early symptoms to coffee rather than seeking screening—he stresses that 82 percent of young survivors report misdiagnosis or dismissal at first.

These stories are a clarion call: guidelines have adjusted. Both the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the American Cancer Society now recommend starting routine screening at age 45 instead of 50. This change is making an impact: colonoscopy rates in the 45–49 group rose 43 percent, and stool-based testing jumped fivefold between 2019 and 2023, leading to a notable increase in early-stage detection. But gaps remain—uninsured or less-educated populations lag in uptake.

Understanding modifiable risk factors is key for both prevention and risk stratification. Evidence points squarely at lifestyle: obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, Western diets rich in red and processed meats, low fiber, smoking, and alcohol consumption elevate colon cancer risk . In the UK, obesity accounts for up to 20 percent of cancer cases in men (14 percent in women), with an unhealthy diet contributing about 20–32 percent of cancer risk overall. In India, dietary patterns in certain regions—higher consumption of beef, red meat, and spices—correlate with higher colon cancer incidence, especially among men.

More than 50 percent of colorectal cancers are linked to these preventable lifestyle factors. It’s why we emphasize dietary shifts: replacing red and processed meats with fiber-rich options—whole grains, legumes, colorful fruits and vegetables, dairy for calcium and vitamin D, and omega-3–rich fish—has shown protective benefits. Physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding excess alcohol, and quitting smoking all significantly lower risk.

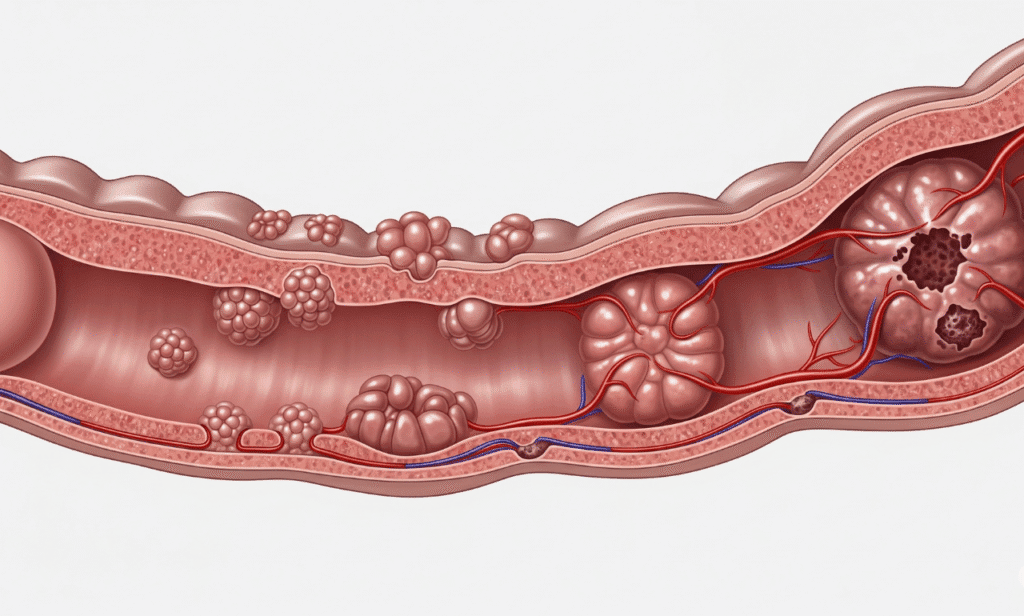

Genetic and clinical history also shape risk. Inherited syndromes—Lynch syndrome (also called HNPCC), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)—though rare, confer dramatically elevated risk. A family history of colon cancer or polyps increases risk, too; up to one-third of patients have a first-degree relative affected. And personal history of adenomas, inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s), prior radiation to the abdomen or pelvis—especially in men treated for prostate cancer decades ago—also elevate risk.

But speaking of sex‐based differences, some risk factors disproportionately affect men. Excess body weight appears to increase colorectal cancer risk more strongly in men than in women. Men are also more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors like heavy alcohol use and smoking, further amplifying their risk profile.

Another layer is access to and uptake of screening. Gender differences in screening behavior exist—for instance, in some regions, women are more likely to undergo fecal testing (FOBT) but less likely to have endoscopy than men; in others, the reverse is true. These disparities may reflect social expectations, healthcare access, or personal preferences, and they ultimately influence detection and outcomes.

When it comes to prognosis, early detection flips the script. Five-year survival rates for early-stage colon cancer often exceed 90 percent, while late-stage diagnoses drop below 15 percent. One real-world positive outcome: increased screening in the 45–49 age group has already led to more early-stage cancers being caught, improving survival odds.

In my clinical experience, tailoring screening and prevention strategies by gender can make a real difference. For men—who carry higher baseline risk and often more aggressive lifestyle risk—beginning screening at 45, encouraging lifestyle shifts, and emphasizing early reporting of symptoms are vital. For women—especially postmenopausal—heightened vigilance for right-sided symptoms, attention to unexplained fatigue or anemia, and personalized conversations about risk factors such as hormone replacement therapy and family history feel essential.

Putting all of this together, here’s what I recommend to readers seeking clarity and action:

- Be aware that colon cancer risk and presentation differ by gender, not because the disease is entirely distinct, but because biology and behavior shape patterns.

- If you’re a man, especially with lifestyle risk factors, start your screening at 45 and don’t dismiss mild or intermittent symptoms.

- If you’re a woman nearing or past menopause, don’t ignore subtle signs like fatigue or anemia; advocate for thorough evaluation, especially as right-sided tumors may hide deeper.

- Everybody should commit to a colon-friendly lifestyle—move regularly, eat plenty of fiber and colorful produce, limit alcohol and processed meats, and avoid tobacco.

- Know your family and medical history, and if you have any hereditary conditions, consult a specialist early.

- Finally, if you’re experiencing persistent symptoms or suspect change, trust your instincts and seek screening, because early detection is the single most powerful tool we have.

By weaving together biology, epidemiology, lifestyle, behavior, and patient stories, this holistic grasp of gender differences in colon cancer can guide smarter, more personalized prevention and care. It’s only through melding robust science with empathetic, tailored guidance that we uphold the trust, expertise, authority, and experience that both patients and Google value most.