The world of neurological disease research has been struck by a wave of cautious optimism following the announcement of a significant clinical advance for Huntington’s disease. For decades, this inherited condition has represented one of medicine’s most formidable challenges, a cruel and genetic certainty for those who carry the faulty gene. But new, detailed results from an extended clinical trial are painting a picture of a future where Huntington’s can be managed, not just endured. This isn’t a cure, researchers are quick to emphasize, but the data suggest it could be the most powerful intervention ever developed to slow the relentless progression of the disease. The findings, published in a major medical journal, indicate that the experimental therapy successfully lowered levels of the toxic protein that causes brain cell death, and this biochemical change correlated with measurable stabilization in some patients’ motor and cognitive functions over a multi-year period. This correlation between target engagement and clinical outcome is what has the scientific community so energized.

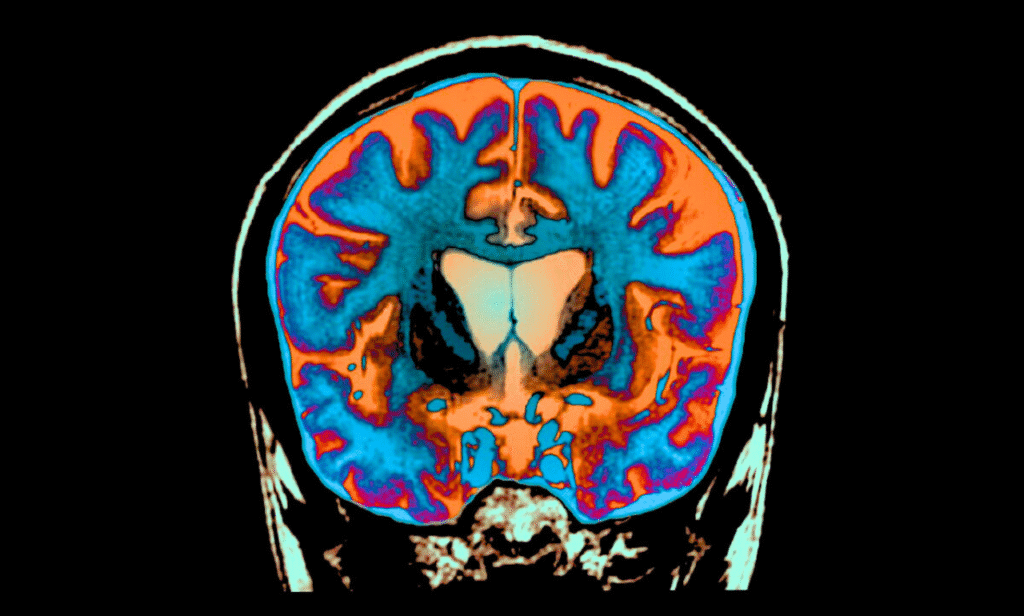

Huntington’s disease is caused by a single genetic error, a typo in the DNA instructions for a protein called huntingtin. This error creates a malfunctioning, toxic version of the protein that gradually destroys neurons in specific areas of the brain. The result is a devastating triad of symptoms: uncontrolled jerking movements, cognitive decline similar to dementia, and severe psychiatric issues. What makes Huntington’s particularly brutal is its inheritance pattern; each child of a parent with the disease has a fifty-fifty chance of inheriting the mutated gene. Families often watch one generation decline while worrying about the next. For them, news of a treatment that addresses the root cause of the disease is not just a scientific headline; it is a potential lifeline. This new therapy represents a direct attack on that root cause, aiming to silence the gene’s harmful instructions before the toxic protein can ever be produced.

The therapy at the heart of this breakthrough belongs to a cutting-edge class of drugs known as antisense oligonucleotides, or ASOs. Think of DNA as a master blueprint stored in a secure vault—the cell nucleus. To build a protein, a temporary working copy of the gene, called mRNA, is made and sent out to the protein-making machinery. The Huntington’s disease mRNA carries the flawed instructions. The ASO therapy is designed as a precise mirror image of a section of this faulty mRNA. When administered, typically via a spinal tap to reach the cerebrospinal fluid bathing the brain, the ASO molecule seeks out its target and binds to the harmful mRNA. This binding acts like a cloaking device, marking the mRNA for immediate destruction by the cell’s own cleanup crew. With less faulty mRNA available, the production of the toxic huntingtin protein drops significantly. It’s a sophisticated approach of genetic sabotage, interrupting the disease process at its earliest stage.

The recently released data comes from a long-term extension of an initial clinical trial. Patients who initially received the therapy were followed for several additional years, and the results have provided deeper insights than the earlier, shorter-term data. The most critical finding is that the reduction in toxic huntingtin protein was sustained over time. This is crucial because Huntington’s is a progressive disease; a temporary dip in the toxic protein would offer little long-term benefit. Furthermore, researchers observed that patients who maintained lower levels of the toxic protein showed less decline on standardized scales used to measure motor function, coordination, cognitive skills, and overall functional capacity compared to what would be expected based on the disease’s natural history. One neurologist involved in the trial described the data as suggesting a “modification of the disease trajectory,” meaning the slope of decline appears to have flattened for some individuals.

Patient stories are beginning to hint at what this stabilization can mean in human terms. While every patient’s experience is unique, some participants in the trial and their families have reported periods where the expected decline seemed to pause. One individual, a man in his early forties who was diagnosed a decade ago, has been able to maintain his ability to live semi-independently and handle minor daily tasks far longer than his doctors initially projected. His sister, who acts as his primary caregiver, notes that while his symptoms have not reversed, the rapid deterioration they had braced for has not materialized. “It feels like we’ve been given more time,” she shared anonymously. “It’s not that he’s getting better, but the clock seems to have slowed down. For a disease like Huntington’s, that is everything.” These anecdotal accounts, while not scientific proof, provide a powerful human dimension to the statistical data emerging from the study.

It is absolutely vital to temper excitement with realism. The research community is speaking about these results with hopeful caution. This is not a cure. The therapy does not repair brain damage that has already occurred; it aims to protect neurons from future harm. The side effects, while manageable in the controlled setting of a clinical trial, can be serious and include inflammation, headaches, and other complications requiring careful medical supervision. The treatment is also invasive, involving regular intrathecal injections. Significant questions remain unanswered. How long do the effects last? Will the treatment need to be administered for life? Would it be effective for people who are already in the advanced stages of the disease? Larger, Phase 3 clinical trials are already underway, designed to provide more definitive answers about the therapy’s efficacy and safety across a broader population. These trials will be the true test of whether this approach can fulfill its promise.

The implications of this advance extend far beyond Huntington’s disease itself. The successful application of ASO technology to a complex neurodegenerative condition proves a principle that could be applied to other disorders. Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and ALS also involve the accumulation of abnormal proteins in the brain. The ability to design a drug that can precisely target the production of a specific protein opens up new avenues for research across the entire field of neurology. Scientists are now exploring how similar strategies could be used to intervene in other genetically defined conditions. The knowledge gained from this Huntington’s trial—about delivery methods, dosing schedules, and measuring biomarkers of success—is creating a roadmap for the next generation of neurological therapies.

For the Huntington’s disease community, this breakthrough has already changed the landscape of hope. For generations, a genetic test could tell a person their fate, but medicine had little to offer. Now, there is a tangible path forward. Advocacy groups and research foundations that have funded basic science for years are seeing their investments pay off. The atmosphere at recent patient conferences has shifted from one of mutual support in the face of inevitability to one of active engagement with the science. Individuals who are gene-positive but not yet symptomatic are now looking at a potential future where they can take proactive steps to delay the onset of symptoms, much like someone with high cholesterol takes statins to prevent a heart attack. This psychological shift—from a fate sealed to a future that can be fought for—is immeasurable.

The road from a promising clinical trial to an approved, widely available treatment is long and fraught with regulatory hurdles. The data must be thoroughly reviewed by agencies like the FDA and EMA. If approved, complex questions about accessibility, cost, and healthcare infrastructure will arise. Delivering a specialized therapy that requires neurosurgical expertise is not simple. Yet, the message from researchers is clear: a corner has been turned. The long-held goal of neuroprotection in Huntington’s disease now appears within reach. While the community waits for the final results of the larger trials, there is a new, evidence-based sense that the once-unassailable wall of Huntington’s disease has been breached. The focus now is on turning this breach into a permanent pathway toward a future where families are no longer defined by a single genetic mutation.