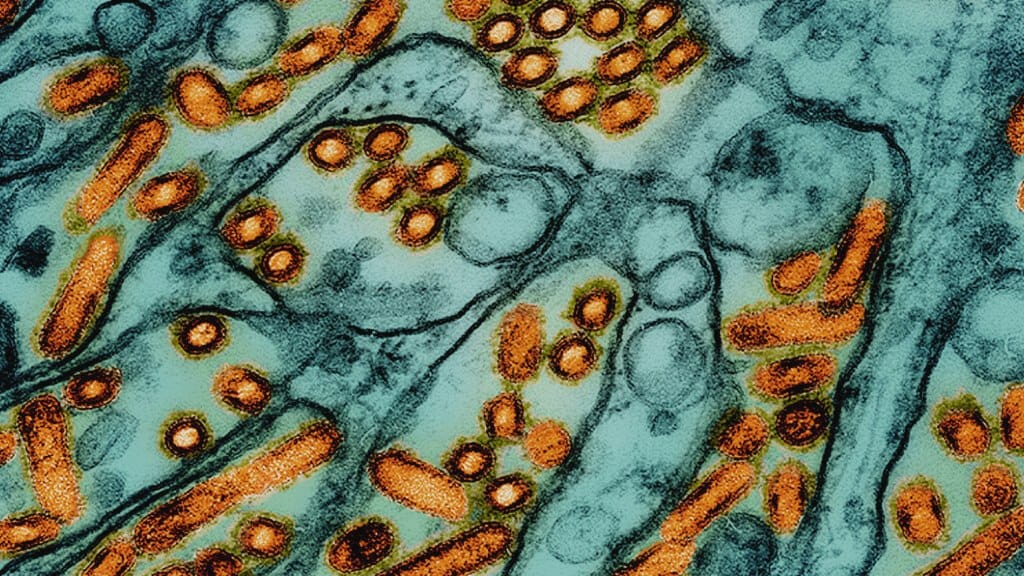

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, remains one of the most closely watched public health concerns worldwide. Recent developments in Louisiana have added a fresh layer of urgency to ongoing discussions about how H5N1, the current strain causing the largest outbreaks in birds, might adapt in ways that could affect humans. In southwest Louisiana, a patient was hospitalized with what health officials confirmed as a severe case of bird flu—the first such illness reported in the United States. Although the virus is known primarily for infecting poultry and wild birds, certain strains have been detected in mammals as well, including, in some cases, domestic cats and even humans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (C.D.C.) and other global health organizations have been keeping a close eye on these scattered cases because every new human infection is a potential chance for the virus to learn new ways of spreading among people.

The situation in Louisiana drew significant attention when health workers swabbed the patient’s nose and throat to track any genetic changes in H5N1. Viruses often mutate, and many of these mutations amount to small, insignificant shifts. Others, however, can enhance the virus’s ability to bind to human cells, replicate, or become more transmissible from person to person. The C.D.C. reported that some of the genetic samples from the Louisiana patient indeed contained mutations that could theoretically help the virus infect people more efficiently—specifically by allowing it to enter cells in the upper respiratory tract. Similar concerns had arisen just a month earlier when a teenager in British Columbia, Canada, was diagnosed with bird flu. Like the patient in Louisiana, the Canadian teenager had severe symptoms and required intensive treatment on a ventilator. This common thread raises the question of whether these mutations could signal a broader shift in how avian influenza adapts to humans.

Scientists interpret these findings with both caution and context. The presence of mutations in samples from the Louisiana patient was identified relatively late in the infection process, which suggests that the virus might have picked up these alterations while inside the human body rather than acquiring them out in nature. The virus taken from the backyard poultry flock that infected the patient did not display those mutations, and this is somewhat reassuring. It indicates that H5N1 viruses circulating among wild birds and poultry have not, so far, widely acquired the specific mutations that make human transmission more likely. But as experts point out, every time a person becomes infected, the virus gets another chance to adapt to human cells. It’s not a process anyone can fully predict. Mutations that crop up sporadically in one patient may not necessarily show up in another, and many are “dead ends,” meaning they do not help the virus survive or spread. However, the more often these infections occur, the greater the odds that the virus could stumble upon a mutation or set of mutations that significantly enhance transmissibility between humans.

Historically, H5N1 bird flu does not pass easily between people. Instead, most infections happen when a person has close contact with infected birds, whether by handling sick poultry or by inhaling droplets and dust contaminated with the virus. The outbreaks currently plaguing farms have led to culls of poultry flocks to limit the virus’s spread. The geographical range of these outbreaks is substantial, and the economic consequences—most notably the spike in egg prices—have been felt by consumers across the country. Several states, including California, have declared states of emergency as they tackle infections among poultry and, in some cases, dairy cattle. Although that might sound unusual, some reports have mentioned bird flu infections in livestock such as cows, which, while less common, highlight the virus’s capacity to cross from one species to another. With each cross-species infection, scientific interest grows about whether this virus could become better adapted to infecting mammals in general and humans in particular.

In Oregon, for instance, authorities recently reported that a house cat had contracted bird flu and ultimately died. According to officials, the cat was fed frozen raw-turkey chow contaminated with the virus, highlighting yet another pathway by which the virus can jump to mammals. The pet-food manufacturer responsible for this raw product later issued a recall after tests confirmed the presence of the virus. This type of event underscores how widely distributed the virus can become when infected birds are introduced into supply chains. Many people who follow these updates find it disconcerting, but public health officials emphasize that these infections in mammals remain relatively rare and sporadic. Nevertheless, each incidence of cross-species transmission is significant to virologists because it offers the virus an environment to adapt in unexpected ways.

As for the Louisiana patient, specific details regarding their current condition have not been made public. The Louisiana Department of Health has declined to comment on the patient’s status or the exact timing of the nasal and throat swabs. Typically, tracking when samples are taken can help scientists understand if the virus was mutating early on—potentially making it more contagious—or if the virus changed course later in the infection, perhaps as the patient’s immune system mounted a response. The timing can also influence whether these mutations are found at high levels throughout the virus population in the person’s body or if they appear only sporadically in a minority of viral particles. In the case of the Louisiana patient, these mutations emerged in the later stages of infection. The C.D.C. notes that such changes, while concerning, might be less worrisome than if they had been present right from the start, because early-stage mutations would have a higher chance of enabling spread to close contacts.

In a broader sense, scientists are looking at how H5N1 might become more adept at attaching to human cells in the upper respiratory tract. Seasonal flu viruses excel at that, which is one reason they spread so readily via droplets and aerosols. If H5N1 were to develop that ability on a large scale, the consequences could be dire, given its severity in many infected individuals. The mortality rate for bird flu in humans who do get sick is historically much higher than that of typical seasonal flu strains, though part of that is because only the most serious infections tend to be detected. Still, the severity of individual cases—from the Canadian teenager on a ventilator to previous outbreaks in Asia that caused high fatality rates—makes this virus particularly ominous in the eyes of virologists.

One possibility experts worry about involves reassortment, a process in which two different flu viruses infect the same host and exchange genetic material. If a person, for instance, were infected with both H5N1 and a seasonal influenza strain at the same time, the viral particles could swap genes. This could produce a novel influenza virus with the transmissibility of seasonal flu and the higher pathogenicity often associated with H5N1. Although this scenario is hypothetical, it’s the exact type of event that global health agencies monitor because it might serve as a spark for a pandemic. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan, noted that with every new infection, the virus gains a fresh opportunity to adapt or swap genes. She has emphasized that the virus’s potential to do harm on a large scale remains very real, especially if it gains efficient human-to-human transmissibility.

Even now, large numbers of people in the United States face some level of direct exposure risk. Farmworkers, veterinarians, and others who handle poultry or livestock regularly come into close contact with animals that might harbor bird flu. The infections seen in the U.S. this year have mostly stemmed from such direct contact, although the virus does not seem to spread beyond that immediate exposure. Public health agencies often remind the public that properly cooking poultry and pasteurizing dairy products inactivate viruses like H5N1, rendering them safe to eat. Still, the downstream economic impacts—like higher egg prices and disruptions in the food supply chain—demonstrate how a highly pathogenic avian influenza strain can ripple through an industry and affect everyday life.

Regarding prevention and control, the situation underscores the importance of comprehensive surveillance and vaccination strategies. One key revelation in the C.D.C.’s announcement is that the strain found in the Louisiana patient closely resembled candidate vaccine viruses. Researchers and vaccine manufacturers maintain these candidate strains to be ready at a moment’s notice should a mass vaccination program become necessary. While that is reassuring, some experts, including Dr. Rasmussen, question why these vaccines are not being used now to immunize people who face the highest exposure risks. The reasoning is that every human infection is a potential stepping stone for viral adaptation. Vaccinating farmworkers, cull teams, veterinarians, and other high-risk groups could, in principle, reduce the risk of the virus mutating in a human host. One argument against widespread vaccination is that current H5N1 vaccines might not be a perfect match for a future mutated strain, and rolling out mass vaccination campaigns can be logistically complex and costly. However, some scientists argue that having even partial protection in at-risk groups is better than allowing the virus to circulate unimpeded among those who work in close proximity to infected animals.

Many international organizations are also strengthening guidelines and best practices around biosecurity for farms. This includes restricting access to poultry houses, mandating protective clothing for workers, increasing testing, and isolating any bird showing symptoms of disease. While these measures cannot guarantee that no infections will occur, they drastically reduce the likelihood of large-scale outbreaks. Farmers and agricultural workers are encouraged to remain vigilant and report unusual bird die-offs, so state and federal agencies can conduct tests and implement containment measures quickly.

On a more personal level, public health experts advise anyone who keeps backyard birds or exotic birds to follow recommended guidelines for sanitation and veterinary care. Simple measures—like washing hands thoroughly after handling animals, wearing gloves and masks in coops, and ensuring the living environment is kept clean—can go a long way toward reducing risk. In communities where bird flu has been detected, health authorities might also recommend heightened caution for pet owners, especially those who feed their pets raw meat diets. The Oregon case of the cat that died after consuming contaminated frozen turkey stands as a reminder that the virus can be found in unexpected places. Pet owners in areas experiencing outbreaks may want to consult veterinarians about whether to switch to diets unlikely to pose that risk.

Beyond individual measures, global health officials emphasize the need for sustained surveillance and international collaboration. Influenza viruses do not respect borders, and wild bird migrations can carry them from one continent to another. That’s why agencies like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) encourage member countries to report outbreaks promptly. Transparency can help scientists track the virus’s evolution in real time and issue warnings about new strains or worrying mutations that might appear in birds, mammals, or humans. Rapid sharing of data ensures that vaccine research can keep pace with changes in the virus. Given the unpredictability of influenza viruses, continuous updates to candidate vaccine strains remain a vital part of pandemic preparedness plans.

In the U.S., the C.D.C. has a dedicated influenza division that closely monitors both seasonal flu and avian flu cases. Laboratory networks exist to analyze viral samples quickly, allowing officials to detect any changes that might signal an increase in transmissibility or severity. The report that mutations appeared in the Louisiana patient’s viral sample triggered an immediate investigation. Fortunately, no evidence so far indicates that the virus spread from this patient to others. That said, the vigilance must continue. As Dr. Rasmussen pointed out, it’s good to have candidate vaccine viruses on hand, but there should be a deliberate plan about how and when to deploy them, particularly for individuals at the greatest risk of infection. Coordinated public health planning could reduce the possibility of a dangerous new strain emerging and might prevent future severe cases like the one in Louisiana.

Another dimension of avian influenza management is the economic and emotional toll it takes on farmers and rural communities. When outbreaks happen, entire flocks might need to be culled. This can mean financial ruin for smaller farms and impact the broader agricultural economy. Some backyard poultry keepers also become attached to their birds, which adds an emotional burden when mandatory culling orders are issued. Consequently, officials strive to balance disease control with humane treatment. Various compensation and reimbursement programs may exist, but they are not always sufficient to offset the losses. These challenges highlight why proactive efforts—such as improved sanitation, vaccination of birds where feasible, and better diagnostic tools—are so crucial.

Scientists continue to explore the underlying biology of avian influenza viruses to better forecast how they might change. A key factor is the structure of proteins on the virus’s surface, like hemagglutinin (the “H” in H5N1) and neuraminidase (the “N”). These proteins determine how the virus binds to cells and how it releases new viral particles. Mutations that change the shape or function of these proteins can alter how the virus interacts with specific host receptors, including those in human airway cells. While some changes are beneficial to the virus, others can weaken it, so not every mutation is necessarily bad from our standpoint. Nonetheless, the worry is that eventually, the virus might stumble upon just the right combination of mutations that make human-to-human spread more feasible.

Environmental factors also play a role in how influenza evolves. Dense poultry farming operations can act like incubators for viral spread and adaptation because so many birds live in close quarters. Wild bird populations, especially waterfowl, act as reservoirs for flu viruses that migrate long distances. If a highly pathogenic virus emerges among wild birds, it can spread rapidly across countries and even continents through migration routes. Efforts to monitor wild bird populations include collecting samples from birds found dead or appearing ill, with wildlife agencies testing them for bird flu. Such surveillance can give a warning if a more dangerous variant emerges in wild bird populations, potentially alerting authorities to ramp up protective measures before the virus hits domestic poultry or livestock.

In Louisiana, the patient’s case marks a sobering reminder that avian flu remains an evolving threat. While the patient’s virus did acquire certain mutations, there’s no indication at this time that they were enough to enable easy person-to-person spread. Still, it’s one instance among a growing list of incidents worldwide where H5N1 has jumped to humans or other mammals. That is precisely why health officials will continue to push for tight monitoring of both human and animal cases. Laboratory testing for flu viruses in hospitalized patients with severe respiratory illness can spot these infections early, and contact tracing can then determine if any secondary cases arise among close contacts.

The larger lesson is that bird flu, in many ways, exemplifies the unpredictable and interconnected nature of infectious diseases in a globalized world. The virus started primarily in birds, but a combination of intensive agricultural practices, wildlife interactions, and international trade has given it room to adapt in surprising ways. As of now, there is no evidence that these worrying mutations seen in Louisiana are becoming widespread in nature. But the next step is always uncertain. For the general public, the advice remains straightforward: continue to cook poultry products thoroughly, practice good hygiene, and be aware of emerging stories about outbreaks near you. For policymakers and health officials, the burden lies in deciding how best to prepare for a potential scenario in which H5N1 or a similar avian influenza strain becomes more contagious among humans. That preparation includes everything from shoring up vaccine supplies and ensuring distribution networks are in place, to minimizing the frequency of human infections through robust biosecurity measures on farms.

There is no simple, single fix. The question of whether the H5N1 virus in its current form can kick off a global pandemic remains unsettled. Experts do not expect that it can jump from person to person easily—at least, not yet. But the virus has shown a capacity for adaptation, and nature has a way of surprising us. The best strategy is layered: reduce the risk of bird-to-human transmission by controlling outbreaks in poultry and wildlife; vaccinate at-risk populations when viable; strengthen surveillance to catch new infections early; and maintain global networks that share data and resources rapidly. In doing so, health authorities around the world can better position themselves to respond quickly if an outbreak of H5N1 or another novel flu strain begins to show signs of efficient human-to-human spread.